Coal, man and voidness.

Text and photo: Ilya Pilipenko

There is a peculiar calendar in Novokuznetsk. Time is often measured by the tragedies here. That’s what people say: “when “Ulyana” blew” or “after “Raspadskaya”. In the line of the past the names of the mines in the black frames are the absolute and objective units of time measurement. I remember these endless funerals myself, traffic jams caused by the funeral processions, wreaths, wet snow on the black suits and on the faces burnt by another accident. Those memories are the distinct and almost perceivable border which separates “before” from “after”.

Almost every mine has a stela with the names of the victims of the accidents. Wreath-laying ceremony is one of the administration’s responsibilities. According to the official statistics there is one human life for each million tones of the mined coal in Russia. Dispassionate numerals equal the mountains of black rocks shining on the sun with the living human with his habits, family, soul. Only number. Then these units (in the local mining language – zero units, meaning the died and brought up by the rescue men after the explosion) are identified by the rings and keys and buried with honors. The widows receive compensation. And few more names add to the monument. It’s almost ordinary life here.

Almost every mine has a stela with the names of the victims of the accidents. Wreath-laying ceremony is one of the administration’s responsibilities. According to the official statistics there is one human life for each million tones of the mined coal in Russia. Dispassionate numerals equal the mountains of black rocks shining on the sun with the living human with his habits, family, soul. Only number. Then these units (in the local mining language – zero units, meaning the died and brought up by the rescue men after the explosion) are identified by the rings and keys and buried with honors. The widows receive compensation. And few more names add to the monument. It’s almost ordinary life here.

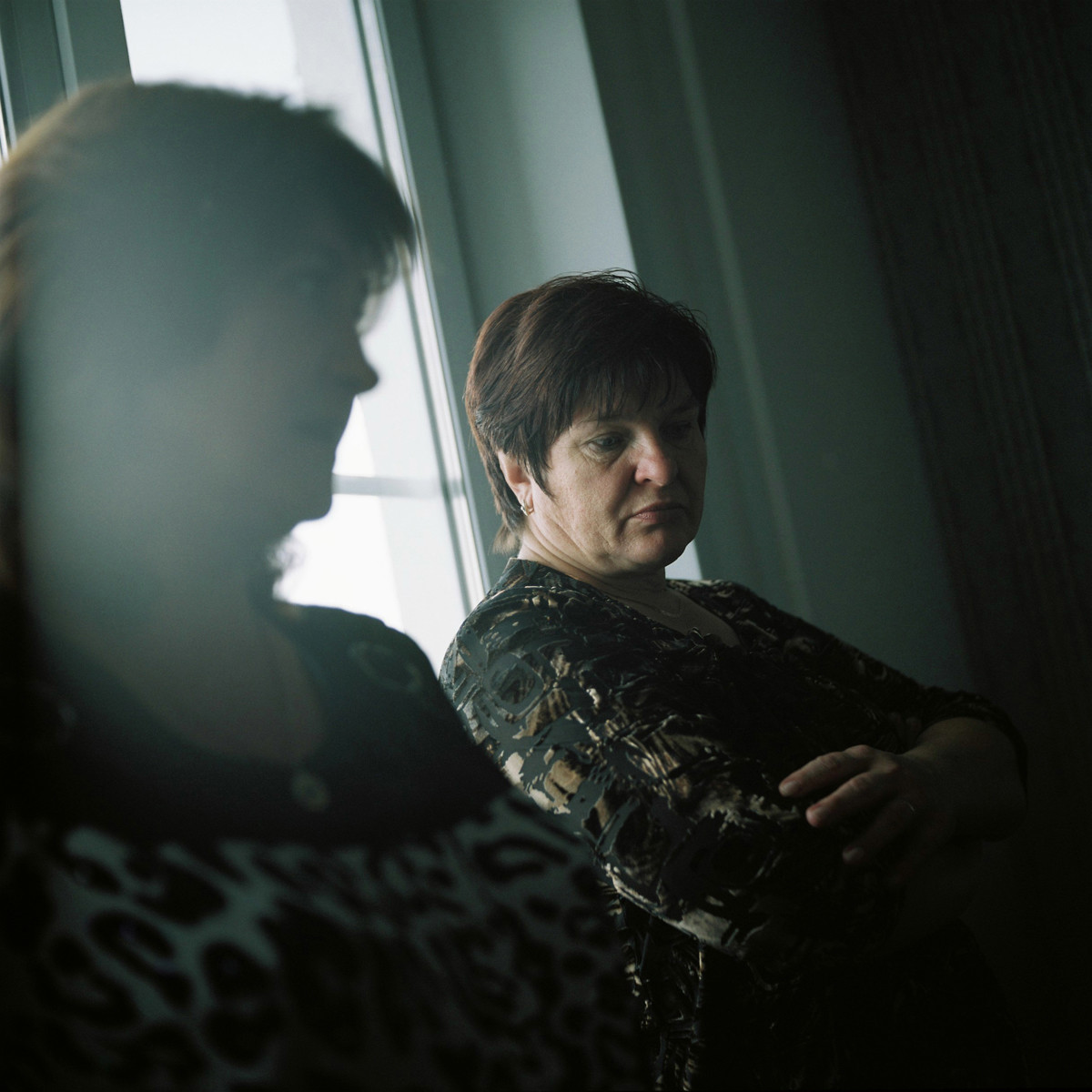

Rusty monument “Miners Glory” is standing near the gateway to the city district where several mines were working, now all of them are closed. Near one of these closed and destroyed mines the Kondratievs house is standing. Sergey Andreevich, who has worked underground for 23 years, says: “I’m living within one hundred meters from the mine, there is no mine anymore, but still there is me and I’m happy and glad.” Everything is ordinary: the Army, then work – “and the young man went to the mine face” – life is like a song. He’s also telling that he lived his life in this place and it was very convenient to work near home, and how the whole street was celebrating the holidays. He looks older than he is. His wife is nearby – Irina Yurievna, twisting an apple in her hands, listening for the same story for the thousandth time. They are recalling the past calmly and with the certain pride. Sergey Andreevich says that, despite of all, every night he sees the mine in his dreams, and in his dreams he is getting ready for work. In reality the remains of the mine are guarded by the same ex-miner as he. Irina is sighing.

She is telling that there are voids under their house, like in all private housing here. These voids are caused by the mine working. I’m listening to their intermissive story and trying to imagine that unknown voidness. I think that hard and dangerous work of many years is doing the same with the man. It is leaving the voids, which need to be filled. And everyone is filling them in his own way. Valeriy Pavlovich Prokopiev, a family friend, is also here. He is also a former miner. After leaving the mine he became a member of the “Church on the Stone”. He says: “I have evidences that God has been preserving me, there was no accident during all 13 years of work.” He looks afraid and calm at the same time.

She is telling that there are voids under their house, like in all private housing here. These voids are caused by the mine working. I’m listening to their intermissive story and trying to imagine that unknown voidness. I think that hard and dangerous work of many years is doing the same with the man. It is leaving the voids, which need to be filled. And everyone is filling them in his own way. Valeriy Pavlovich Prokopiev, a family friend, is also here. He is also a former miner. After leaving the mine he became a member of the “Church on the Stone”. He says: “I have evidences that God has been preserving me, there was no accident during all 13 years of work.” He looks afraid and calm at the same time.

One is filling his emotional emptiness with the memories, another – with faith.

They are the special caste. Those who didn’t work underground can never fully understand why this profession is changing the person so much. Eyelashes blackened with the coal dust (which is impossible to wash out) are not the issue. The issue is in some special attitude toward death and life. Their everyday work is like a war. “Hot days of work, similar to the battles” – from the same song. Which other industry has it’s own medal? And the miners have “Miner’s Honor” of three classes – the remains of the world, in which the value of life and heroic deed could be measured by the tone of coal and length of service. Now we have monetary units for this. May be it’s good that now labor is only labor. But something else is needed except money, and now small money, by the way.

This voidness because of the loss and getting back to work after it (because there is no other place to go) and, which is more important, the voidness caused by the lack of the meaning – everyone has it. And everyone has the stories which cannot be told. And what indeed we can understand, we, always staying at the surface. There are lots of stories about different things, but also about the same thing – about the happy and the sad, safe and mutilated, working and retired, about the price of the labor and about the priceless – about the nonzeroes.

This voidness because of the loss and getting back to work after it (because there is no other place to go) and, which is more important, the voidness caused by the lack of the meaning – everyone has it. And everyone has the stories which cannot be told. And what indeed we can understand, we, always staying at the surface. There are lots of stories about different things, but also about the same thing – about the happy and the sad, safe and mutilated, working and retired, about the price of the labor and about the priceless – about the nonzeroes.

Leave a Reply