The oldest functioning hydroelectric plant in Russia.

Text and photos by: Ekaterina Tolkacheva

Translated by: DM

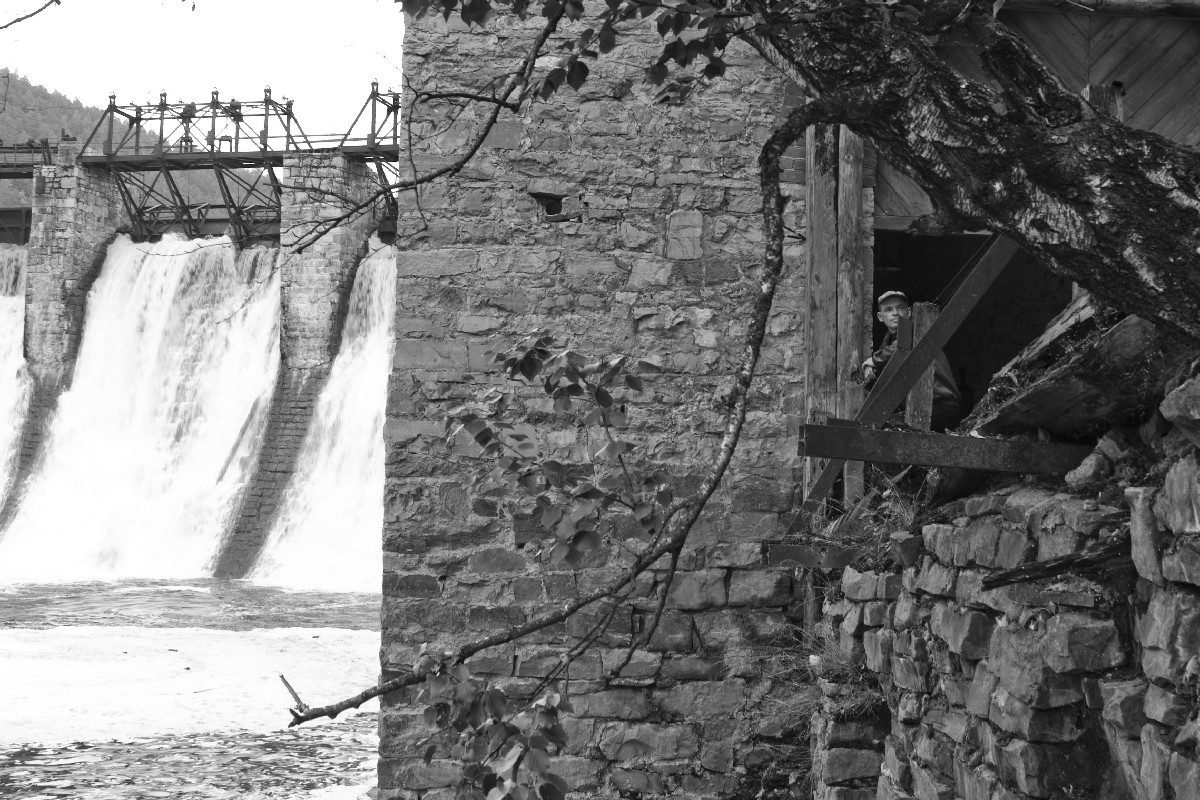

An everpresent rush of water from the dam outside accompanied by a steady drone from the generators inside — this is what you hear at the Porogi (Rapids) hydroelectric plant — the oldest working hydro plant in Russia. It is located on the Satka river 42 kilometers from the city bearing the same name.

It started operating in 1910 along with the first Russian electroferroalloys processing factory, and was intended to supply it with power. The name of the facility and workers’ town comes from the rapids and the rocky river bed, now hidden in the pond of the dam.

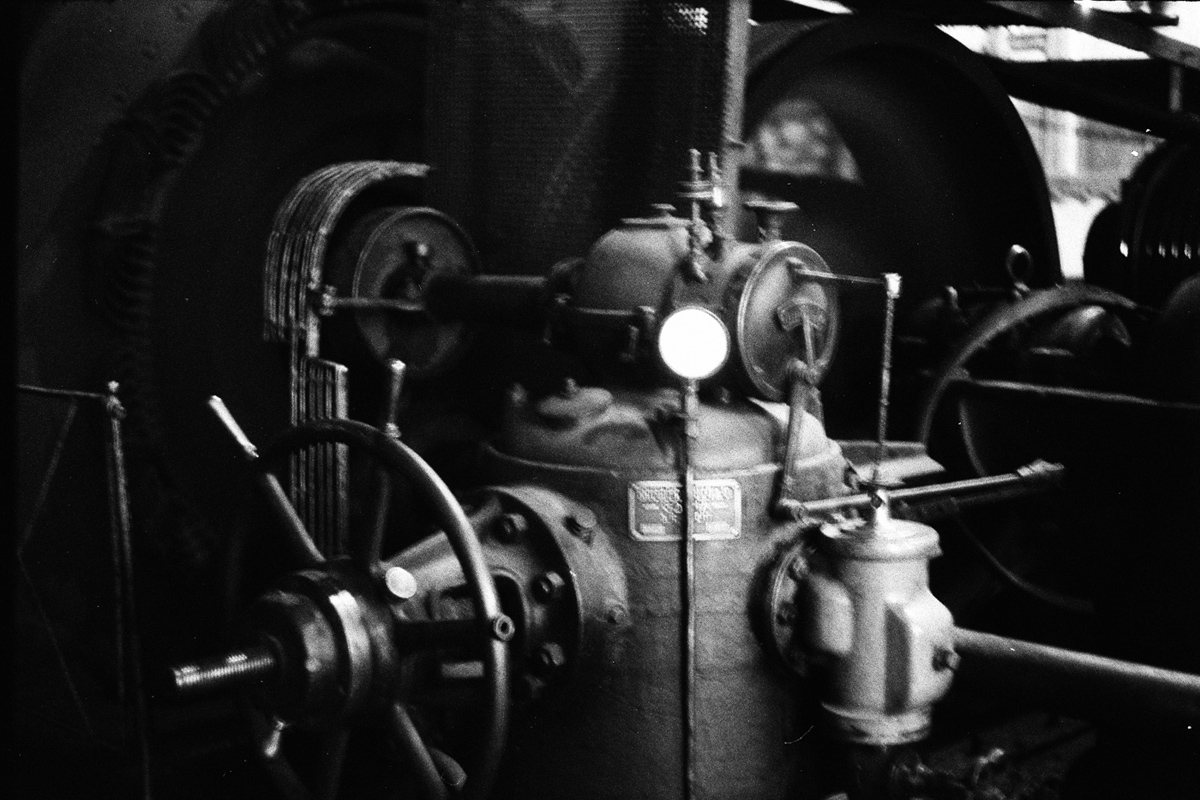

This is all a dear child of a mining engineer Alexander Filippovich Schuppe. He could have been remembered as a revolutionist but, luckily enough, he was more into his own trade than revolutionary ideas. After graduating the Mining Institution he was sent to Ural, far from political unrest, all the closer to industrial work to be done. After being promoted to chief manager of Satka factory, then Zlatoust factory as well, he became one of the founders of a “trust companionship” which was the first in the Empire to establish magnesite mining. Inspired by this success, Schuppe took on a new challenge, as he was to build an electroferroalloy factory. Back then, its production was dangerously explosive and took a profound knowledge of physics and chemistry, with a fair bit of courage, of course. The factory was developed together with the electric plant, to cut down production energy costs. The plant was in those days called a ‘hydroelectric installation’. The dam was built under supervision of a world scale hydrotechnics engineer — Boris Alexandrovich Bakhmetev. The turbines were made in 1909 on an individual request by Briegleb, Hansen & Co in Gotha city, Germany. One of these turbines is still running with no major repairs.

Before the Revolution in 1917 the electroferroalloy factory was a commercially successful private enterprise. After the Revolution it was attached to Satka ironworks and up till 1931 remained the only factory of this profile. It was then included as part of the ‘Magnesite’ plant and started producing high quality firebrick, which continued till 2001. All this time the HEP kept working with no interruptions, not even stopping when the production has been considered unprofitable.

Today it only supplies power to Porogi town, Postroiki village and a hotel near the dam, built by ‘Magnesite’s former engineer in charge Victor Zagnoiko. He had sold his share of Magnesite JSC stock in 1997 and decided to try himself in hotel business. The landscapes and views of Porogi caught his eye the most. Without this circumstance, the HEP would probably be an industrial ruin by now — a common sight in Ural. But Zagnoiko contracted to service the plant and the dam on his own funds, receiving back power for his hotel and, apparently, moral satisfaction. “People these days will bustle about with a decorated historical mansion, which even a highschooler could reproduce in 3D. Try building a dam like this, for a change! Indeed it is a monument to Russian engineering”. The monument these days is a representation of how an industrial object can perfectly fit the landscape.

The engine room is where the turbine operators take shifts, listening to the water flowing and generators humming. I arrive at Alexander’s shift, we’re sitting in a small store room enjoying some tea. He keeps glancing at the ampere meter dial once in a while. As soon as there’s a deviation in parameters, he goes to the engine room to make some adjustments. “Something just turned on in the hotel”, — he comments. I soon notice I can’t help following his example and keeping the meter in sight. Once you forget it’s alarming indicating hand, it’s easy to imagine all the machinery in the room working on its own accord with no need of human supervision.

The engine room is where the turbine operators take shifts, listening to the water flowing and generators humming. I arrive at Alexander’s shift, we’re sitting in a small store room enjoying some tea. He keeps glancing at the ampere meter dial once in a while. As soon as there’s a deviation in parameters, he goes to the engine room to make some adjustments. “Something just turned on in the hotel”, — he comments. I soon notice I can’t help following his example and keeping the meter in sight. Once you forget it’s alarming indicating hand, it’s easy to imagine all the machinery in the room working on its own accord with no need of human supervision.

I notice a turning lathe. No big deal. The spare parts to make repairs with are no longer produced, so they have to adapt what they have. The recent repair, Alexander says, had him screw more bolts than ever in his life.

The storeroom’s walls are like windows to heaven — lush ladies painted by an unknown artist appear to look at you from another world. In times past people would make a steamy banya here, so the beauties’ bodies are now flaking off with the moisture.

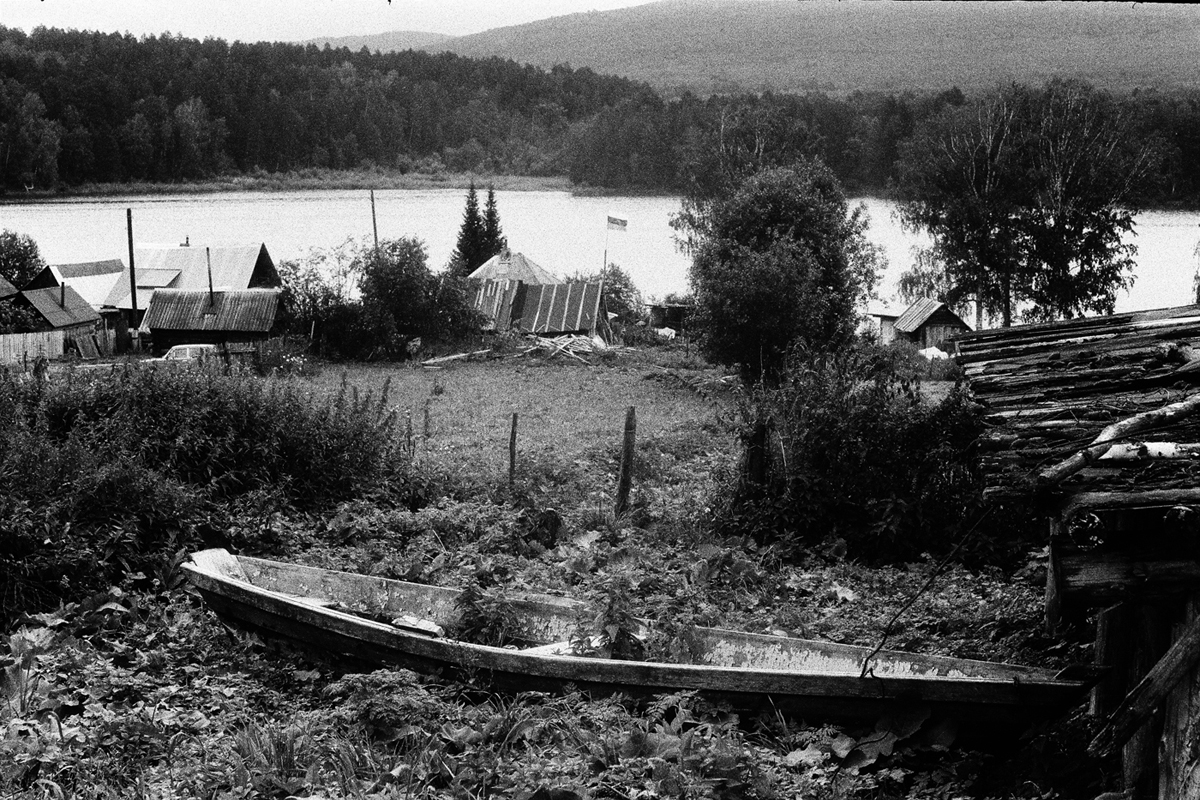

Alexander was born in Satka and after quite some roaming settled in the secluded village of Postroiki, a little way off the Porogi town. There’s no shops here, no proper roads, but this is where his household is, and a whole lot of spare time, too. You can even find your love here. Alexander’s pals from the city sometimes bring mail, and this is how he met Galya — through a newspaper announcement. Galya, a tram driver from Chelyabinsk, came to this remote place — and stayed with him. It’s a beautiful place. Electric shutdowns are an often issue in winter, though. Sometimes the water level drops, other times the obsolete network can’t handle the load from heaters turned on in the few houses supplied by the Porogi HEP.Porogi has been built as a workers’ town for the factory, and now consists of a few dozens of houses, mostly up for rent as dachas. The secluded and spectacular position is the main attraction for city dwellers, and thanks to them, this place is coming back to a new life. Porogi are part of the tourism development program in Satka area but not everyone is happy about it. Those who dwell here at the moment are refusing the civilization willingly, and don’t really want it to reach them at all. As long as there’s no proper asphalted road and power line, this place won’t be swarming with tourists, the municipal administration comments with some regret. But no tourists means no funds to service the dam which has seen no repair in the last 100 years. The town council’s funds simply can’t afford it.

So for now things remain the same, but most importantly, there’s hope and even conviction that some day this monument to Russian engineering and German quality will find its investor.

So for now things remain the same, but most importantly, there’s hope and even conviction that some day this monument to Russian engineering and German quality will find its investor.

Leave a Reply